|

The Peer Review System:

Is Climate Science Politically Corrupt?

by

John L.

Daly

(Written

during January, 2004, published February 22, 2004.)

The Greenhouse Industry

On this website, frequent reference has been made to the so-called

`Greenhouse Industry'. The term itself implies that scientists and

policy-makers involved in climate change gain an economic benefit from

over-emphasising the theorised effects of man-made `global warming'.

That such a benefit exists is undeniable - consider the explosive growth

of climate-related research institutions and academics in the last 25

years, with all the opportunities for travel to exotic locations for

conferences and the improved prospects for promotion which exists. This

is one of the few sciences where a kind of Hollywood `star' system

applies, where fame and applause greets those scientists who tell the

industry exactly what it wants to hear. This star system is the very

antithesis of science, yet is encouraged quite blatantly by the industry

and its leading body - the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(UN-IPCC).

Stephen Schneider, Ann Henderson-Sellers, Phil Jones, Ben Santer, Tom

Wigley, and most recently Michael Mann, are the most notable examples of

this star celebrity system operating in climate science.

The New Censorship

But what makes this distortion of science possible in the climate

sciences? The key reason appears to be the censorship of ideas which has

taken place via the traditional scientific `peer review' system. The

system of `peer review’ was established during the nineteenth century as

a means to uphold quality control in science and to exclude patently

flawed science from the publications of the scientific community, known

as `journals'. This of course involves something of a trade-off between

the wider social values of free speech and the narrower values of

preserving the integrity of science itself.

The ideas and papers excluded from the journals in this way could always

be published in non-scientific publications so that the censorship only

really applies within the journal community. Since the emergence of the

internet, it is now possible for anyone to publish material without

editorial interference - something seen as a dangerous curse by some, and

an opportunity for genuine free flow of ideas by others. In this new

environment, science has taken a backward step in defence of its

privileges vis-a-vis publication of papers and ideas. Scientists are

increasingly refusing point blank to entertain any new knowledge or ideas

as being in any way valid *unless* they are published in one of their own

journals. Since scientists and their institutions have privileged access

to policy makers in government and industry, it amounts to an arrogant

assertion of a monopoly over knowledge itself.

Once any monopoly is established, abuse and corruption soon follows, and

it is the climate sciences which have led the way down that dangerous

path.

The climate sciences are the most politicised of all the sciences, with

intense public debates raging about both the existence of, and extent of,

`global warming', with over $4 billion spent in the US annually on

research into this real or imagined phenomenon. It is in this

politically charged atmosphere that `peer review' has exposed its dark

ugly side, the use of a system of quality control which works passably in

other sciences, but which has become in the climate sciences a ruthless

instrument of censorship by one partisan school of ideas against any

dissent to its supremacy.

Here is how the system of censorship works -

A scientist or group of scientists (or lay persons) may author a paper

intended for scientific publication and submit it to one or more of the

recognised journals for publication. This is done in the sure knowledge

that unless it appears in a journal, it will be summarily dismissed

without further thought by the scientific establishment. In other words,

it is journal publication or oblivion for whatever ideas or knowledge the

author is intending to impart.

The journal editor (or sub-editor in the case of the larger journals)

consider the paper and make a quick and ready judgement about whether the

paper might be suitable for publication at first glance. This is the

first censorship hurdle as the prejudices of the editor can influence the

decision. If the editor is satisfied the paper might be acceptable, he

or she sends it out to `referees', usually two or three reviewers known

to be expert in the same field as the subject matter of the submitted

paper, these reviewers being selected by the editor. The choice of

reviewers itself may also be open to editorial bias.

The reviewers have enormous power. They act in complete anonymity and

can recommend for or against the paper, and few editors will go against

their judgement. They will provide comments and reasons for their

decisions, but there is no appeal. In other words, the paper's prospects

for publication rest entirely with two or three possibly prejudiced

individuals acting in complete anonymity and safe from any criticism of

their decision. The author has no idea who these referees are - they

could be rivals, or they could be ideologically hostile to the subject

matter of the submitted paper. The referrees by contrast know full well

who the author(s) is and are easily swayed if the authorship originates

with a prestigous institution.

In a politically charged environment like climate science, the scope for

abuse of this system is obvious. Both the editors and reviewers are

quite liable to act as upholders of a partisan orthodoxy and reject any

paper which questions the basis for that orthodoxy. It is a profoundly

subjective process, vulnerable to abuse and all done with no transparency

behind the veil of anonymity. The system is an impregnable coward's

castle.

It is little wonder that `climate skeptics' have little confidence they

would receive fair treatment under such a system when there is a vast

global self-interested industry ranged against them.

In my 2002 trip to the USA, I gave several talks to university groups. I

was challenged several times to submit my critical views in the form of

papers or `comments' on papers to the peer-reviewed journals. My

response was usually that (a) the process would take months, meaning that

I would be unable to give an immediate reaction to a contemporary event,

(b) there was no guarantee that it would get past the industry's own

reviewers, and (c) opinions expressed in my comments and papers would be

met with censorship by reason of their position, not because of quality

considerations. But while I put that view, I had never really tested the

system to see if my low opinion of it would be borne out in practice.

To test it properly, it was necessary to wait until I had an

`open-and-shut' case to present, something which could not possibly be

objected to on credible scientific grounds. Such an opportunity

presented itself in April 2003 when the scientific journal Geophysical

Research Letters published a paper on the Isle of the Dead sea level

benchmark, an issue with which I had intimate familiarity.

Peer Review and Censorship - A Case Study

Further discussion about the scientific and historical issues relating

to the `Isle of the Dead’ can be read via

Sea Levels:Isle of the Dead

Very briefly, the Isle of the Dead is a small 2-acre island inside Port

Arthur harbour in southeastern Tasmania. In 1841, the Antarctic explorer

Captain Sir James Clark Ross was responsible for establishing a survey

mark on a cliff on the island, which he said (several times) marked `zero

point, or the mean level of the sea’.

The sea level benchmark is still there in full view, but now lies not at

mean sea level (MSL) as Ross said, but at a point 31 cm above MSL. The

documentary evidence surrounding the establishment and later position of

this mark is both contradictory and inconclusive. However, a paper by

Hunter et al appeared in GRL purporting to demonstrate that the mark

really shows that sea level rose at the Isle of the Dead by around 9.8

mm/yr, which just happens to match the IPCC lower estimate of 10 mm/yr

global sea level rise during the 20th century.

My own study of the benchmark reached a very different conclusion to that

of Hunter et al, and demonstrated very little sea level rise at all at

the Isle of the Dead. The details of that controversy can be seen here,

but that controversy is not in itself the issue under discussion now.

In the course of their paper, Hunter et al sought to reinforce their

pro-IPCC scenario by comparing sea level data at the Isle of the Dead

with Hobart, Tasmania, some 50 km away. It was in making this comparison

that Hunter et al made fundamental academic errors, at one point invoking

the support of data which did not actually exist. They made three key

errors -

1) They cited a reference for Hobart sea levels which I checked and found

to be irrelevant to what they were claiming. A dud reference is not what

academics of any discipline should knowingly do. 2) They presented

graphical sea level data for the period 1875 - 1889 which on further

examination was found to be non-existent. 3) They presented error

estimates for this non-existent data.

It was exactly the `open-and-shut’ issue which provided an opportunity to

test out the bone fides of the peer review system, so I decided to submit

a 2-page `comment’ to GRL. `Comments’ are not full research papers but

criticisms or supplementary information to published papers. Comments

face exactly the same editorial and peer review hurdles that normal

papers do, but are generally much shorter. A comment provided the means

to test the system without committing excessive resources to what would

likely to be a fruitless exercise anyway.

There ensued an exchange of emails with the editors of GRL, which was

followed two weeks later with a formal submission of my comment

(hyperlinks in the comment are active)

My `Comment’ to GRL

|

Comment on "Hunter, J., Coleman, R., Pugh, D., The

Sea Level at Port Arthur, Tasmania, from 1841 to the Present, GRL,

v.30, no.7, 1401, Apr. 2003"

Submitted to Geophysical

Research Letters by Mr. John L. Daly,

Launceston, Tasmania

Proprietor of "Still

Waiting for Greenhouse" website

< http://www.john-daly.com

>

Abstract

A recent paper in this journal by Hunter et

al presents results of a study into historic sea levels in southern

Tasmania. It suggests a rise in mean sea level (MSL) since 1905 at

Hobart, Tasmania, based on a comparison between modern MSL and an old

`state datum’ based on tide data taken in Hobart prior to 1905. The

only reference they cite as their source of information about the `state

datum’ is a 1941 report by a Standing Committee for the Tasmanian

Government that gives no information about the height, accuracy, or the

time line used in its determination. Hunter et al also present

MSL data from 1875 but provide no evidence to support the existence of

Hobart tide data prior to 1889.

The Tasmanian State Datum

Hunter et al [2003]

show a Tasmanian `state datum’ in their Fig.2 from 1875 to 1905 and

its estimated uncertainty range for this 30-year period. They twice

cited a Tasmanian Government report dated 1941 [DPIWE,

1941] as the only reference to support the existence and status

of that `state datum'. However, that report contains no technical

information about this datum (not its height, not the years of data

involved in its calculation, not the method of determination, not even

the existence of a `state datum’ at the time the document was written

(1941)). The only information it contained was that a local MSL datum

from the Hobart Marine Board existed.

The cited document says that in 1940 the

Australian Defence Department asked the then Tasmanian Government to

establish a unified network of land-based benchmarks for the purpose of

surveying landmarks, etc. The State Government responded by setting up a

`Standing Committee' of representatives from key government departments.

No marine or port authorities were represented.

The Standing Committee proposed that all survey

benchmarks in Tasmania be referenced against one master benchmark (B.M.

No.1), and that other survey benchmarks be established all across

Tasmania, height referenced to BM No.1. One sub-committee recommended

that BM No.1 should not be height referenced to the old Hobart Marine

Board MSL datum, but instead referenced to MSL at Derwent Bridge Head [p.15],

where a tide gauge already existed with readings kept `over a period of

years' [p.8]. No other details were given about either MSL datum.

The full Standing Committee later rejected the

Derwent Bridge proposal and instead opted for the older Hobart Marine

Board datum, mainly because it was already in widespread use by the

Hobart City Council for its survey maps and other property survey

documents [p.18].

The Minutes of that Standing Committee’s meeting

on August 20th 1940 explain that the proposal to use the

Hobart Marine Board MSL datum for statewide use was a recommendation for

a future survey policy, not something that then existed. (The

pertinent extract from those minutes is attached as Appendix A). The

committee appeared indifferent to the actual height of MSL, in that they

opted for convenience over exactness. Prior to these meetings in the

1940s, there was no `state datum' as such.

Since the 1941 document cited by Hunter et al, did

not give any details about the `state datum’, or provide any follow-on

references, information was sought from the Surveyor-General's office of

the Department of Primary Industries, Water & Environment (DPIWE) in

Hobart [N. Bowden, DPIWE, pers. comm. 2003].

Following the 1941 report, the Government of

Tasmania incorporated the committee's recommendations in the `Survey

Co-Ordination Act 1944'. This led to the establishment of BM No.1 and it

was defined as being 35.45 feet above MSL, based on the Hobart Marine

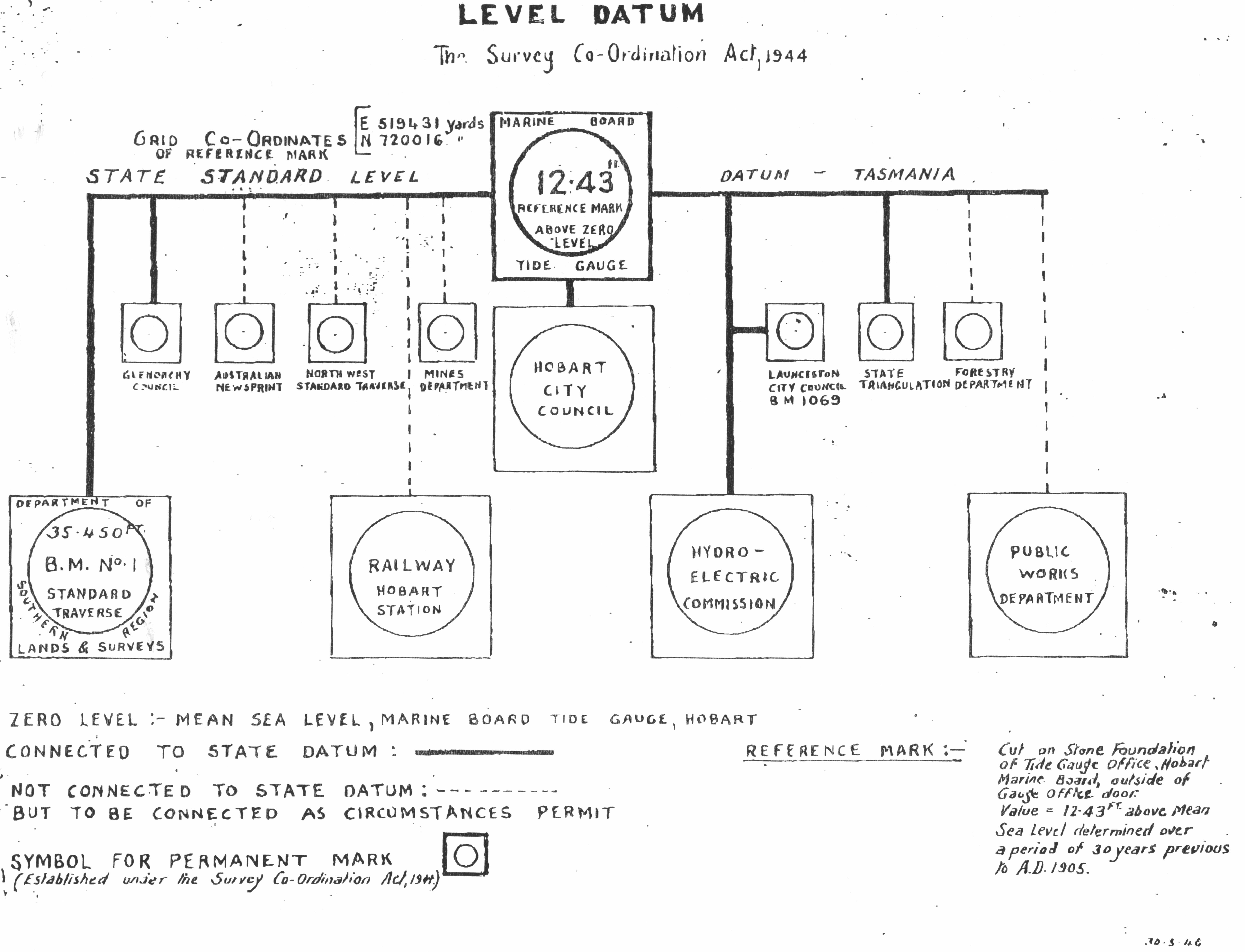

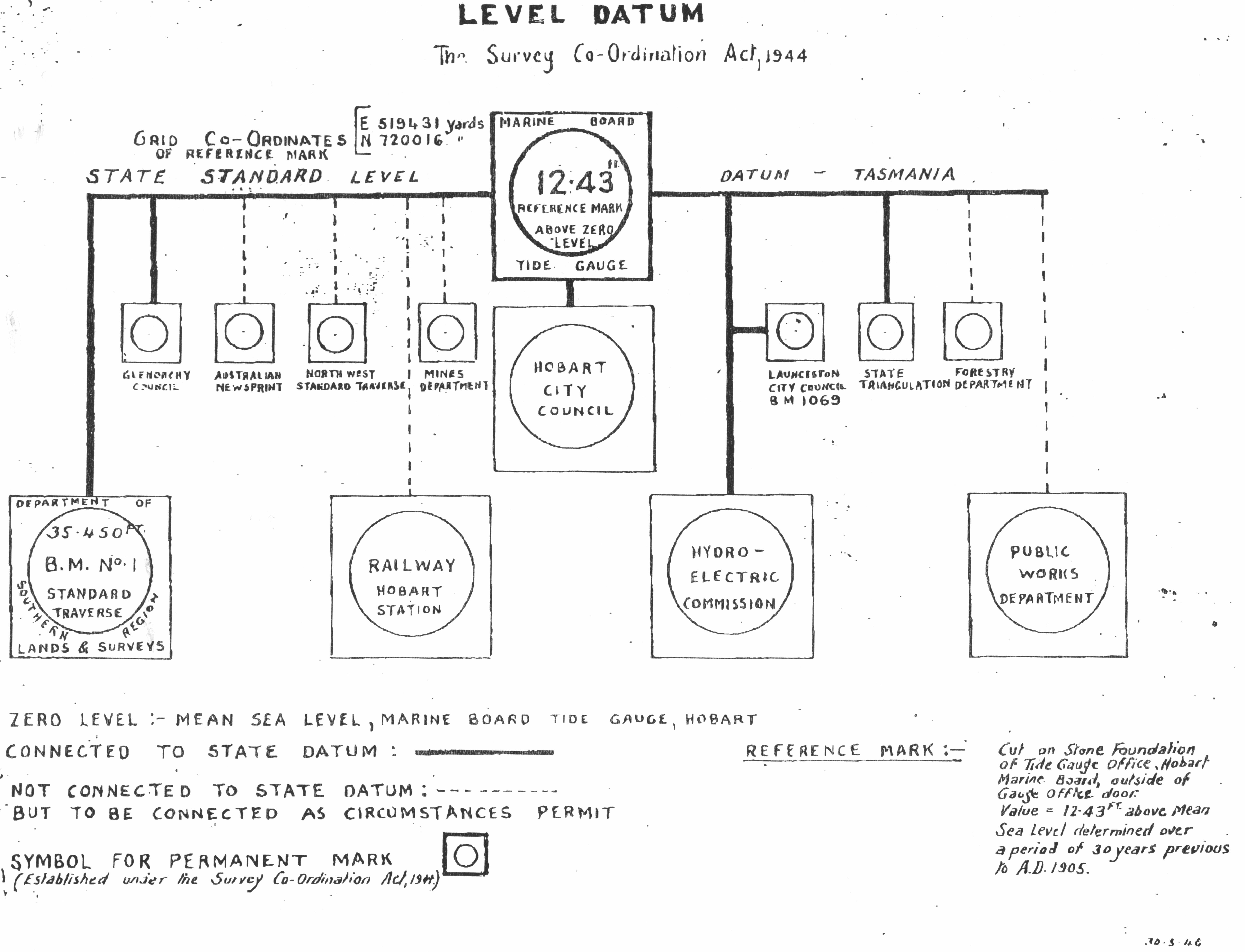

Board datum. The new scheme was summarized in this 1946 `station diagram’

from the Surveyor-General’s Office in Hobart [DPIWE,

1946].

Fig.1 The station diagram defining

the Tasmanian State Datum

BM No.1 (on the left of Fig.1) was defined as

35.43 feet above MSL (the thick connecting line), MSL being determined

from a `reference mark' (top center) that is stated as being 12.43 feet

above the `state standard level’ (representing MSL). However, it is

not now known how these heights above MSL were calculated, or by whom.

The information relevant to Hobart sea levels is

the height datum given by the `reference mark' and - more importantly -

the small note at the bottom right of the document titled `Reference

Mark 'that says:

"Cut on Stone Foundation of Tide Gauge

Office, Hobart Marine Board, outside of Gauge Office Door. Value = 12.43

ft above mean sea level determined over a period of 30 years previous to

A.D. 1905."

This note is consistent with the `state datum’

line and the 30-year time span as shown by Hunter et al. However,

the authorship and methodology of this station diagram is unknown and

was not separately cited by Hunter et al. The diagram is the only

known original reference to the height of the `state datum’. This

level was declared the `State Datum' in 1946, not 1905 as suggested by

Hunter et al, and remained that way until the Australian Height

Datum was adopted in 1972 [Hunter et al, 2003].

The 12.43 ft height of the `reference mark’

above MSL at the Hobart tide gauge pre-1905 cannot be authenticated

today. The old tide gauge hut from which that datum was determined still

exists, but the tide gauge mechanism has gone and there is no surviving

information about the type of gauge used [Bowden,

DPIWE, and Ridgeway, CSIRO, pers. comm. 2003]. Only

a stilling well for the water remains. Numerical data from it exists but

the height of the tide gauge zero is unknown. In other words, the

measurements themselves are not referenced to anything, and the

absence of the mechanism in the hut means the original zero reference

cannot now be determined.

Hunter et al say (abridged) -

"In 1905, the Tasmanian State Datum was

defined, based on observations of mean sea level at Hobart, Tasmania …

for the previous 30 years [Government of Tasmania, 1941]…we have

estimated the mean sea level … for 1875-1905." [Hunter, 2003]

The document they cite [DPIWE,

1941] shows that a `Tasmanian State Datum' did not exist as such

in 1905. Instead, there was only a local Marine Board of Hobart datum.

Therefore the phrase "In 1905, the Tasmanian State Datum was

defined..." is not correct as the definition and adoption of a

`state datum' was not introduced until 1946.

The 30 years of data from 1875 to1905 presented by

Hunter et al. in their Fig.2 and the 1946 station diagram are

inconsistent with other information regarding tide data from Hobart.

Mault [1889] reported in the Royal

Society of Tasmania journal that due to a lack of previous tide

information about Hobart at that time, he borrowed a tide gauge from a

visiting ship and mounted it on New Wharf, Hobart, to collect tide data

during February 1889. According to Mault -

"Please note that these observations are only

for one month, and that, as probably the mean tide level varies at

different seasons, to get satisfactory results, a year's observations

should be obtained - this could easily be done with an automatic gauge.

I am glad to say that this will be done, as the Hobart Marine Board is

taking the necessary steps to procure and fix such a gauge.

It was from 1889, not 1875, that the Hobart Marine

Board began systematic tide measurements, largely prompted by Mault’s

study. The Surveyor-General's office [Bowden, pers.

comm. 2003] and the CSIRO [Ridgeway, pers.

comm. 2003] confirmed that to their knowledge, the pre-1905

data from the Marine Board tide gauge began in December 1889, not 1875,

consistent with Mault’s statements in his 1889 paper.

This key point about the start date for Hobart

tide data is also affirmed by the websites of the Intergovernmental

Oceanographic Commission [ www.bodc.ac.uk/services/glosshb/stations/gloss056.htm

] and the NOAA

[ www.nodc.noaa.gov/woce_V2/disk09/glosshb/gloss056.txt

], both of whom say - "Previous gauges have operated in

Hobart since 1889." The National Tidal Facility website

[ www.ntf.flinders.edu.au/TEXT/MCDD/BLUEPAGES/61220.html

] at Flinders University, South Australia, says - "Observations between 1889 and December 1994 exist.

The observations may not be continuous over this time period."

However, Hunter et al stated they

"have estimated the mean sea level relative to the benchmark for

1875-1905" and charted this on their diagram with an

uncertainty range estimated by them back to 1875.

This statement, and their charting of the results,

is inconsistent with the information from these other sources which

establish 1889, not 1875, as the start date for tide data in Hobart. The

only known reference to the years 1875-1889 comes from the anonymous

note on the 1946 station diagram [DPIWE, 1946] which

says MSL was `determined over a period of 30 years previous to AD 1905',

with no further details given. This apparently incorrect information in

the note must then raise questions about the credibility of other

information contained in the station diagram, including the accuracy of

the `state datum’ itself.

Fig.2 of Hunter et al includes an

uncertainty range estimate for 1875-1889. This presupposes the existence

of sea level data for that period from which an uncertainty range could

be calculated. However, they provide no reference to or source for that

data. (During a Royal Society of Tasmania discussion on Mault’s paper [Mault, 1889], one society member recalled that a

local school headmaster had previously kept a register of tides around

1853, but that details of this had been lost by 1889. Another member

said he too had registered the tides `at one time’. There is no record

of either data set today).

Conclusion

The paper by Hunter et al does not provide

any referencing support about historic sea levels in Hobart, or the

years involved, nor the 1875 start date they indicated. Since no other

references were offered to clarify the issue, the claims about the

Tasmanian `state datum’ in that paper cannot be viewed as meeting

scientific criteria.

Appendix A

"Recommendation No.1 - Establishment of State

Government B.M. No.1

Mr. Foster (Engineer,

Hobart City Council) considered that it

would be preferable to adopt the M.S.L. datum as established by the

Hobart Marine Board, and to which all the City of Hobart Corporation

levels were already referred, rather than adopt the M.S.L. at Derwent

Bridge, which had only lately been determined.

Col. lane (Forestry

Department) agreed that, as the City Council's system of levels

already covered a considerable area, Mr. Foster's proposals should

receive consideration. The Chairman (Mr. Pitt, Secretary for Lands) stated that it would not be of great importance which

plane of approximate M.S.L. was adopted as zero so long as its position

was clearly defined and a zero value permanently assigned to it for all

State levels."

Acknowledgements: My

thanks to N. Bowden of the Surveyor-General’s Office, Hobart,

Tasmania, K. Ridgeway of the CSIRO Division of Oceanography, Hobart, and

to Richard Courtney, London, for their valuable assistance in providing

information and documentary material on the history of tide measurement

in Hobart.

References

Dept. Primary Industries Water and Environment (DPIWE),

Office of the Surveyor-General, Government of Tasmania, Report and

Proceedings of the Standing Committee of the Coordination and

Correlation of Levels and Surveys in Tasmania, Government of Tasmania,

January 1941, Hobart, Tasmania

(Online copy available here)

DPIWE, Land Services Division, SPM1371 Survey

Control Mark Station File, Hobart, 1946

Hunter, J., Coleman, R., Pugh, D., The Sea

Level at Port Arthur, Tasmania, from 1841 to the Present, GRL, v.30,

no.7, 1401, Apr. 2003

Mault, A., On Some Tide Observations at Hobart

During February and March, 1889,

Royal Society of Tasmania, p.8, 1889

The above `comment' was declined

for publication by Geophysical Research Letters,

publishers of the original Hunter et al paper to which it refers. |

Supporting documents were provided with the comment for the assistance of

the reviewers, in particular the document which Hunter et al made a

reference to, but which was both irrelevant and provided none of the

information about the subject matter being referred. One of these was a

government report and the other was a copy of Hunter et al’s graphic.

The Peer Review

After a 6-week wait, I finally received the following email from GRL

declining my comment for publication. It was no surprise as it was much

what I expected. Of more interest were the twisted reasonings offered by

the editor and reviewers for rejecting the comment, in effect upholding

the flawed science they had themselves published months earlier.

Following are the editor's concluding comment, and the two reviewer's

evaluations.

We have had your manuscript, 2003GL018288, "Comment on Hunter, J.,

Coleman, R., Pugh, D., The Sea Level at Port Arthur, Tasmania, from 1841

to the Present, GRL, v.30, no.7, 1401, Apr. 2003," reviewed for both

scientific content and GRL-specific criteria. Based on this evaluation,

unfortunately I cannot accept your manuscript for publication in

Geophysical Research Letters. Both reviewers feel (and I agree) that

there is insufficient substance in your comment as it stands to warrant

publication. In order for a comment to be published, it needs to clearly

indicate a mistake or misinterpretation in the original paper. It also

needs to do so in a concise and terse manner as space in GRL is tightly

constrained. In the current case, a non-critical element was, for

understandable reasons, not cited as completely as it might have been in

the published GRL paper.

Attached below are the review comments, which you may find helpful if you

decide to revise your document and submit it as a new comment to GRL or

elsewhere. I am sorry I cannot be more encouraging at this time.

Reviewer #1 Evaluations:

Science Category: Science Category 4

Presentation Category: Presentation Category C

Annotated Manuscript: No

Anonymous: Yes

Referrals: No

Highlight: No Preference

Reviewer #1(Formal Review):

The author criticizes the manner in which the State Datum for Tasmania is

referred to in the analysis of Port Arthur sea level by Hunter et al.

(2003)(henceforth HCP). Apparently, the datum was not officially

referred to as the "State Datum" until the 1940s, and not in 1905 as

implied in HCP. There is also concern expressed regarding the source

(anonymous) and length (30 years or 16 years?) of data used to specify

the datum. The author concludes that ". . .the claims about the

Tasmanian 'state datum' in that paper cannot be viewed as meeting

scientific criteria."

The whole issue of when the datum in question was referred to as the

"State Datum" may be of historical interest, but it has little impact on

the results presented in HCP. I also do not share the author's concern

about the validity of the datum itself. It seems hard to imagine that the

datum would be accepted as the "State Datum" without some faith at the

time that sufficient care was taken in establishing the original height

above mean sea level. Likewise, if the datum were grossly in error, it

seems unlikely that this error would not have been detected and corrected

after almosta century of development.

I do not recommend publication of this comment unless the editor feels

that the discussion of historical details, here and in the reply by Hunter

and his colleagues, provides an interesting supplement to the HCP paper.

I don't find that the scientific issues raised are particularly

important.

Reviewer #2 Evaluations:

Science Category: Science Category 4

Presentation Category: Presentation Category B

Annotated Manuscript: No

Anonymous: Yes

Referrals: No

Highlight: No

Reviewer #2(Formal Review):

Review of Daly Comment:

-----------------------

The comment submitted by Daly to GRL is very weak.

If it was printed (but it is far too long as it stands), Hunter et al.

would have no problem refuting it. It is trivial. However, it may be

desirable to publish a short version (maybe one paragraph) and let Hunter

refute it in another short paragraph.

As to detailed comments on the submission, the whole thing is too long.

It boils down to:

(1) Daly asserting that the Tasmanian State Datum, referred to at the

bottom of column 1 of page 2 or the Hunter et al. paper, was referenced

incorrectly to the Government of Tasmania report of 1941 and not to a

one-page datum diagram drawn in 1946.

(2) The statement in that one-page that the datum was based on MSL data

for 30 years ending in 1905 could not have been correct as no decent

gauge existed for all of that period at Hobart.

In the case of (1), I guess Daly is strictly correct, although I suspect

I might have done what Hunter et al. did and just reference that report

(which is referenceable document) and not the one-page (which isn't or at

least would have to be referenced in a very grey way), especially given

the space restrictions in GRL. In principle though, I agree that Hunter

could have referenced the one page also.

However, none of this matters a hoot as it has no impact on the main

theme of the paper which is the Port Arthur 1841-2 data. Also there is

no disgreement that this is the same datum everyone is referring to, even

if the referencing could have been more complete.

In the case of (2), even if one takes Daly's story at face value that

there was no decent gauge there before 1889 (although no one knows for

sure), Hunter was making a reference to the claimed origin of the datum

which implied that indeed there was, which just leads us back to point

(1).

Incidentally, the quotes from 3 websites on page 5 of Daly's Comment are

all in effect from the same source (the Australian National Tidal

Facility) who provide the information to the GLOSS Handbook web page, of

which the NODC page is a copy.

|

And that was it. GRL and its chosen reviewers had rejected the comment

for no valid scientific or academic reason, giving purely spurious

reasons for rejection. In doing so, they were effectively saying it was

ok to publish papers with dud references, non-existent data, and even

calculations surrounding that non-existent data.

It meant the Hunter et al paper was deemed `scientific’, while the

comment which exposed its real faults was effectively censored by the

very same system which approved the Hunter et al paper to begin with.

Since I am not a professional scientist, there were no career, economic,

or status implications if my comment was accepted or rejected by GRL.

Besides, there was already an expanded version of it published on my

website here. The purpose of the comment was therefore to test the

impartiality of the peer review system itself when confronted with a

clear and unambigouous complaint against one of its own papers, a test it

failed.

In other words, it was a useful exercise in its own right to determine if

peer review had really become a vehicle for censorship as suggested by

the experience of others. If effective quality control had been applied

by GRL’s peer review process, the Hunter et al paper would have been

rejected for publication, not the comment which exposed its faults.

|